|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

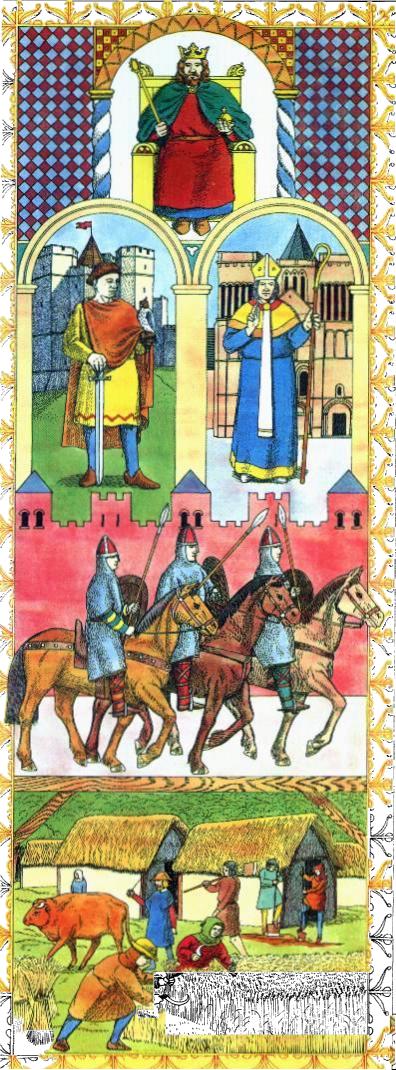

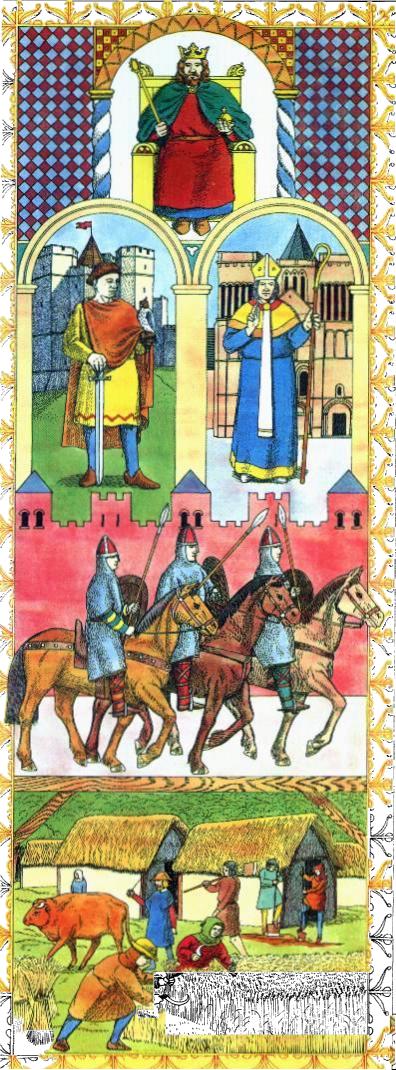

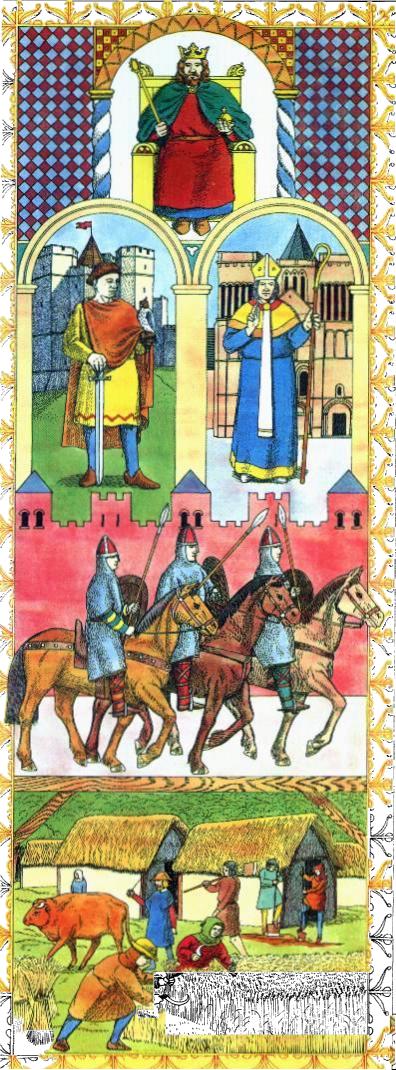

At the time of the accession of King John (1199), England was run on the feudal system, which had been introduced by William the Conqueror and was still in operation. The feudal system was based on the idea that every person in the land had a lord to whom he was owed loyalty and certain services. At the top of this pyramid-like system was the king, and below him were the clergy and barons who owned a substantial amount of land. In return for this ownership they became the king's 'vassals' and swore obedience to the king. Known as tenants-in-chief, these men had the right to pass on land and privileges to their other tenants - usually knights - while in return the knights had to swear obedience and fight for their lords when necessary. Then came the 'villeins', some of whom did duty in return for small amounts of land, while a very few of the lowliest held no land but worked just for their food and shelter.

Although

the king was overlord, he relied upon his powerful barons to provide men

from their lands to fight in the royal army and help provide a steady income

of money. This money was provided in the form of taxes to supplement the

royal coffers - always emptied by expensive wars. For some years, the barons

had been unhappy with the level of taxation.

Although

the king was overlord, he relied upon his powerful barons to provide men

from their lands to fight in the royal army and help provide a steady income

of money. This money was provided in the form of taxes to supplement the

royal coffers - always emptied by expensive wars. For some years, the barons

had been unhappy with the level of taxation.

John's father Henry II had made great demands on the barons' resources in order to fund his continental wars, and Richard I (his brother) asked even more for his crusades. Although the barons were displeased with the situation, they remained loyal to the Kings because they won glorious battles and were seen to be strong and powerful rulers.

Born in Oxford on Christmas Eve 1167, John was

the eighth and youngest child of the infamous 'Devil's Brood' of Henry

II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Like his brother, the great warrior Richard

the Lionheart, he was wild and undisciplined as a child . He grew up a

feckless, irresponsible youth, always in the shadow of his father Henry

and his brother Richard I . He had always been a vain young man and as

king he was able to indulge all of his passions. He was particular about

personal cleanliness and took baths more often than most people in those

days. But fine clothes and jewellery interested him most of all and he

owned vast quantities of both. He was cultivated in his tastes and fond

of books - he always carried a small travelling library with him as he

journeyed. Perhaps the most curious aspect of his character was his inconsistency.

The nobles and clergy found him thoroughly disagreeable, greedy and uncooperative,

yet he was good to his household whom he liked to see happy and well-fed.

He found it impossible to get on with the barons and nobles whose support

was necessary in order to run the country. Instead he chose his friends

and advisors from the lower ranks with whom he felt more comfortable.

|

Unlike his father and brother, John was unlucky in war. He lost Normandy to the French and had difficulty controlling the other areas of France over which he was lord. At home he made the mistake of disagreeing with the Pope about the choice of Archbishop of Canterbury, and this, together with John's desire to take church lands for personal profit, eventually led to a bitter conflict with the church and John's excommunication.

Throughout

John's reign, the troubles with the barons and the church continued. Many

contemporaries thought that he was not interested in any one other than

himself, and were prepared to challenge his authority. He died on 18 October

1216, probably as a result of dysentery brought about, so his contemporaries

described, 'by dining on too many peaches and cider'.

Throughout

John's reign, the troubles with the barons and the church continued. Many

contemporaries thought that he was not interested in any one other than

himself, and were prepared to challenge his authority. He died on 18 October

1216, probably as a result of dysentery brought about, so his contemporaries

described, 'by dining on too many peaches and cider'.

|

Hedingham Castle, Essex. The site of one of King John's major battles during the last year of his reign. Robert de Vere, the 3rd Earl of Oxford and owner of the Castle, took up army against John, forcing him to sign the Magna Carta. A French force landed and established themselves at Colchester Castle, not far from Hedingham, but John attacked and the French surrendered. He then laid siege to Hedingham which fell to him in Spring 1216, after a long and fierce resistance. The following year the French recaptured it; but it was restored to Robert de Vere on the accession of King Henry III in 1217. |

John became King in 1199, and straightaway had to fight an expensive war to defend the lands in France which then belonged to the English crown. By 1204 he had lost most of these lands, but for the rest of his reign he tried, without success, to win them back. Also, from 1207 to 1213 John had a great quarrel with Pope Innocent III, which made him very unpopular with many of his subjects. This, together with the great sums of money he demanded for his wars and the cruel way he treated many English people, determined some of the great barons from the north of England to get rid of him altogether.

It was grievances against the King, particularly against his policy of taking too many taxes to fight unsuccessful wars, which drove the barons to revolt, and made them determined to force John to restore what they called 'their ancient and accustomed liberties'.

The final crisis began early in May 1215 when

John told Robert Fitzwalter. who was Lord of Dunmow (Essex) and the leader

of the barons, that he was prepared to grant all they asked. At this point,

however, other great men, notably Stephen Langton the Archbishop of Canterbury,

William Marshall the Earl of Pembroke, and Hubert de Burgh, one of John's

most able and devoted servants, stepped in to reason with the barons. They

persuaded the barons to make their demands less selfish by asking that

the grievances of the lesser feudal lords, the townspeople and even the

peasants should be dealt with as well.

The result of several weeks of discussion was

a document called the Articles of the Barons, which was presented to John

on June 15, 1215, when he met the barons at Runnymede, a meadow on the

banks of the Thames between Staines and Windsor. The King accepted the

Articles and had his seal attached to them to show his agreement. Then

he ordered his clerks to convert the Articles into a royal charter, which

we call Magna Carta. It took until June 19 to prepare the charter and write

enough copies so that one could be sent to the sheriff of every county.

Like the Articles, of which it is a close copy,

Magna Carta itself is a very practical document, but composed in rather

a huryy and not arranged in a very orderly way. Nearly half its clauses

deal with the complaints of the barons, stating exactly what the King is

entitled by custom to do, how much money and how much service he may demand,

how he should deal with estates temporarily in his keeping, and how his

judges should administer the Common Law. The rest protect the rights of

the church, of townspeople and of merchants, lay down standard weights

and measures for the whole kingdom, and lessen the severity of the special

laws which applied to royal areas called royal forests reserved for the

king's hunting. Finally a committee of barons was allowed, by force if

need be, to compel the King to obey the charter.

|

John did not keep his promises, and Magna Carta failed to achieve its purpose at the time because the barons quarrelled among themselves. Afterwards, however, it had an immense influence on English history. This was because it stated clearly that an English king could not govern as he liked. He must govern according to the law. If he broke the law then his people had a remedy; they could use force to make him behave properly. It was Magna Carta which inspired Englishmen to struggle successfully for what it called constitutional government; that is, government according to law.

The critical moment in the City of London's early history came in 1215, the same year as the Magna Carta. The expense of Richard I's many foreign wars had led him to rely on loans from London merchants, in exchange for which the City gained rights of control over the Thames and acquired its first mayor, Henry Fitzailwin.

Aware

of the movement of cities all over Europe towards independent communes,

Fitzailwin and his supporters pressed for self-rule. Complete civic independence

on the continental model could never be achieved; English kings were too

powerful for that. But when Richard's successor King John became mired

in difficulties with his barons, the City forced out of him a charter conceding

an elective mayoralty. It was to be the basis of the City of London's whole

constitutional arrangement. Elaborated over the years, the system has -

through a series of flukes and anomalies - survived down to the present

day.

Aware

of the movement of cities all over Europe towards independent communes,

Fitzailwin and his supporters pressed for self-rule. Complete civic independence

on the continental model could never be achieved; English kings were too

powerful for that. But when Richard's successor King John became mired

in difficulties with his barons, the City forced out of him a charter conceding

an elective mayoralty. It was to be the basis of the City of London's whole

constitutional arrangement. Elaborated over the years, the system has -

through a series of flukes and anomalies - survived down to the present

day.

John, by the grace of God, king of England,

duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and earl of Anjou, to his archbishops, bishops,

abbots, earls, barons, justices, sheriffs, rulers and to all his faithful

subjects, greeting. Know ye that we have gained and by this our present

writing confirmed to our barons of our city of London, that they may choose

to themselves every year a mayor, who to us may be faithful discreet and

fit for the government of the city, so as, when he shall be chosen, to

be presented unto us or our justice (if we shall not be present); and he

shall swear to be faithful to us; and that it shall be lawful to them at

the end of the year to remove him and substitute another if they will,

or to retain the same, So as he be presented to us or our justice if we

shall not be present ... Wherefore we will and strictly command that our

aforesaid barons of our aforesaid city of London may choose unto themselves

a mayor of themselves, in manner and form aforesaid, and that they may

have all the aforesaid liberties well and in peace, wholly and fully, with

all things appertaining to the same liberties as is aforesaid.

|

He

is known by many different names, including Robin Hood, Robin Wood, Robert

Earl of Huntington, Roberd Hude, Robert Hood, and other variations. Robin

Hood also exists in many forms, simply because his stories were first passed

around by spoken word, in the form of folk tales and ballads dating back

to the 1300's.

He

is known by many different names, including Robin Hood, Robin Wood, Robert

Earl of Huntington, Roberd Hude, Robert Hood, and other variations. Robin

Hood also exists in many forms, simply because his stories were first passed

around by spoken word, in the form of folk tales and ballads dating back

to the 1300's.

Robin stands as the hero of the common people

and yeomans and a symbol of "right against might". Because of the

Sheriff of Nottingham's tyrannical rule and exploitation of the common

people in Nottinghamshire, Robin united his fellow

folk and rebelled against the Sheriff.

Robin is also known for "robbing the rich and giving to the poor."

Some

people say that Robin is high-born, possibly even being the Earl of Huntingdon,

Robert Fitzooth. Kelly Anne Hamel suggests that Robin Hood might instead

have been the Earl of Locksley, who was also known as the Earl of Huntington.

Some

people say that Robin is high-born, possibly even being the Earl of Huntingdon,

Robert Fitzooth. Kelly Anne Hamel suggests that Robin Hood might instead

have been the Earl of Locksley, who was also known as the Earl of Huntington.

"Robert Earle of Huntington

Lies under this little stone.

No archer was like him so good:

His wildnesse named him Robbin Hood.

Full thirteene yeares, and something more,

These northerne parts he vexed sore.

Such out-lawes as he and his men

May England never know agen."

When Richard the Lion Heart returned to England,

only one castle of King John's didn't immediately surrender - Nottingham.

Richard I had to lay siege to the place for three days. And when he was

done, he went hunting in Sherwood. And who was one of the key figures in

the act on Nottingham? Why, the Earl of Huntingdon! Although he was really

David, not Robin Hood."

BACK TO THE TOP